Machinability and Wear of Aluminium Based Metal Matrix Composites by MQL - A Review

Ankush Kohli*1  , H. S. Bains2, Sumit Jain3 and D. Priyadarshi1

, H. S. Bains2, Sumit Jain3 and D. Priyadarshi1

1Dept. of Mechanical Engineering, DAVIET, Jalandhar, India.

2Dept. of Mechanical Engineering, SSGIRIPU, Hoshiarpur, India.

3Dept. of Mechanical Engineering, CTIEMT, Jalandhar, India.

DOI : http://dx.doi.org/10.13005/msri/140218

Article Publishing History

Article Received on : 21 Jul 2017

Article Accepted on : 4 Aug 2017

Article Published : 31 Aug 2017

Plagiarism Check: Yes

Article Metrics

ABSTRACT:

Metal matrix composites have exhibited better mechanical properties in comparison withconventional metals over an extensive range of working conditions. This makes them an appealing alternative in substituting metals for different applications. This paper gives a survey report, on machining of Aluminium metal Matrix composites (AMMC), particularly the molecule strengthened Aluminium metal matrix composites. It is an endeavour to give brief record of latest work to anticipate cutting parameters and surface structures in AMMC. The machinability can be enhanced by the utilization of Minimum Quantity Lubrication (MQL) during the machining of AMMC.

KEYWORDS:

AMMC; MQL; Machining; Reinforcement; Wear

Copy the following to cite this article:

Kohli A, Bains H. S, Jain S, Priyadarshi d. Machinability and Wear of Aluminium based Metal Matrix Composites by MQL - A Review. Mat.Sci.Res.India;14(2)

|

Copy the following to cite this URL:

Kohli A, Bains H. S, Jain S, Priyadarshi d. Machinability and Wear of Aluminium based Metal Matrix Composites by MQL - A Review. Mat.Sci.Res.India;14(2). Available from: http://www.materialsciencejournal.org/?p=5828

|

Introduction

Aluminium Based Metal Matrix Composites (Al MMCs) are one of the latest Functional materials having the properties of high wear resistance, good specific strength, light weight and has capable to adjust the thermal expansion coefficient. Al MMCs composite materials are used in constructural, aircrafts and products used in automobiles like piston cylinder, cylinder liner, Brake disc and drum etc. During fabricated of Al MMCs, the Aluminium as a basic material, known as matrix, which is reinforced with ceramic hard particles like Titanium diboride (TiB2), Boron Carbide (B4C), Silicon Carbide (SiC) and Aluminium oxide (Al2O3). It can be used as high length fibres, particulates may be an irregular shape or spherical shape. The properties of the resulting material are controlled by three critical components: the matrix, the interface and the reinforcement.1 However, the properties of a composite depend on the following parameters such as properties of the matrix, properties of the reinforcement, relative amounts, size, shape and distribution of the reinforcement etc.The composite prove advantageous over conventional metals and alloys based ontheir engineering application and quality, safety, fuel economy, emission, styling, performance, ride handling, comfort, recyclability etc.

Manufacture of aluminium MMCs can be ordered into: liquid state, semi-solid and powder metallurgy process. Mass manufactures of aluminium MMCs can be handled all, the more effectively and financially by the liquid state processing i.e. stir casting process or vortex strategy. Stir casting is an appealing handling strategy since it is generally reasonable, adaptable and offers wide determination of materials and preparing conditions. It can support high productivity rates and enable extensive size segments to be fabricated.2 Homogeneous distribution of reinforcement in the MMC was a challenge especially for Al (TiB2) MMC. Uniform distribution of reinforcements and good bonding leads to the optimum properties in the fabrication of MMC.

Difficult-To-Machine Materials

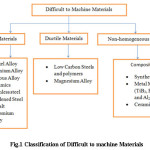

There is no institutionalized arrangement to classify hard to-machine materials with poor machinabilityand their definition is as yet dubious. The discoveries in the writing have grouped the hard to-machine materials into three classifications to be specific: hard materials, ductile materials and non-homogeneous materials. This arrangement and its sub-classes are shown in Fig.1. Although the progress in the fabrication of advanced materials has resulted in enhanced life of the related segments, they have brought about troubles in their processing and machinability. These materials are difficult to machine because of very hard, good quality with low thermal conductivity etc. and after compromising with these results reducing the tool life, productivity and Surface finish.3,4,5 The fundamental issues in machining difficult to machine materials are the formation of chip, precision and surface nature of the machined segments.6,7,8

Figure 1: Classification of Difficult to machine Materials

Composites are difficult to machine due to hard, non-homogeneous and only physically combined particles without involving any chemical reaction. Likewise MMC’s are hard to-machine because of shorter tool lives and poor surface quality. Fabrication of MMC is one task, however further conversion of raw material into useful products/parts of desired shape and size is a different task. Therefore characterizing the cutting parameters to manage the qualities of all materials, individually within a composite material and the entire composite together is exceptionally troublesome. Hard to-machine composites cause extreme tool wear because of hard abrasive particles Such as TiB2, B4C and SiC which are harder than WC tools.9,10 Machining these composites include issues related with their matrix material together with other properties of their particulates, for example, higher quality, higher scraped resistance, higher strength, and so forth.11 The chance of success of aluminium matrix composites relies on their applicability for different machining operations. Machining shares a huge commitment (up to 15%) of the aggregate estimation of manufactured components in the earth.9

In the present era of industrialization, the reduction in the use of metal cutting fluids is a challenge. The environmental concerns limit the use of these fluids due to health concerns. The objective of Health and Safety environment departmental in different areas is to protect the environment against excessive use of these Fluids.12 Chalmers announced that more than 100 million gallons of metalworking lubricants are utilized as a part of the U.S. every year and that 1.2 million employees are exposed to them and to their potential wellbeing risks.As a result, in some cases, cutting oils have been criticized for the dirty work environment caused by them and further for the harmful influence with their disposal on the global environment and this has initiated lot of R&D efforts to create dry cutting methods and introduce them at workplace. Of course Dry cutting, which utilize no cutting oil whatsoever, is one means of contributing to the solution of environment problems, but inevitably it has a lot of disadvantages, such as sacrificing production efficiency or lower production precision and has a limited range of application. Also, when it comes to machining of the aluminium composites, dry machining results in excessive chatter, surface irregularities and excessive tool wear owing to higher temperatures achieved at the tool-workpiece interface. Thus, either we have higher environmental risks with the use of flooded lubrication or we can sacrifice productivity and efficiency by eradication cutting fluid. However, both these situations are not desired as far as the machining of the composites is concerned. Hence, there is a need to employ an intermediate technique.

On the other hand, if we improve the effectiveness of cutting oil, use it only in limited amount, preventing the contamination of the surrounding areas and lastly disposing of it properly, this will enable highly efficient manufacturing and high product precision resulting in environment friendly manufacturing technology.

The three sources of heat generation during manufacturing process are primary shear zone, secondary deformation zone and flank wear zone. In the primary shear zone, major part of energy gets converted to heat; secondary deformation zone at the tool-Chip interface where further heat is generated due to rubbing between tool-chip interface and the third is the flank wear zone which is a result of rubbing between tool and finished surface. The possible detrimental effects of high temperature on cutting tool are: rapid tool wear, plastic deformation of cutting edge, thermal flanking and fracturing of cutting edge, dimensional inaccuracy of workpiece and surface damage by oxidation or rapid corrosion (ME IIT Kharagpur, 2009). During turning operation, high temperature is generated in the region of tool work piece interference. This heat generation is a result of plastic deformation leading to chip formation, friction between tool and workpiece and friction between tool and chip. Cutting tool softens at high temperature, thus thermal dependant tool wear leads to poor surface finish of the product. The amount of heat loss in cutting region is dependent on the thermal conductivity of tool itself and the cooling strategy being applied.13 In order to reduce heat generation for the purpose of quality improvement and cost effectiveness, new cooling approaches have been introduced such cryogenic cooling and compressed air cooling and minimum quantity lubrication.

Minimum Quantity Lubrication (MQL) is a machining applicationin which very small amount of lubricant in mist form is delivered to the cutting zone by compressed air. In MQL machining, heat removal during cutting is achieved mainly due to convection by compressedairand partially by evaporation of cutting fluid. Thislittle amount of lubricant isless polluting, and has few other biological and environmental advantages.14 Minimum Quantity Lubrication (MQL), also known as “Microlubrication”14 and “Near-Dry Machining”,15 is the most recent procedure of conveying metal cutting fluid to the work/tool interface. Utilizing this innovation, somewhat liquid, when appropriately chose and connected, can have a considerable effect on tool performance. In traditional operations utilizing flood coolant, cutting fluids are chosen on the premise of their commitments to cutting execution. In MQL, optional attributes are essential. These incorporate their safety properties, condition contamination and human contact, biodegradability, oxidation and storage stability.MQL can save money, enhance tool life and improve the final part. But it may involve changes to both the tooling and the functional strategy.

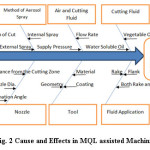

At their ideal working conditions, there is a requirement for machining to accomplish the standard measurement and surface wrap up.16 So, it isproposed that the utilization of MQL upgrades the rebinder impact and in this manner diminishes the work because of plastic distortion.17 Conceivable parameters and machining conditions influencing the execution of MQL machining are delineated in fishbone outline as presented in Fig.2.

Figure 2: Cause and Effects in MQL assisted Machining

Machining of Materials

Some of the problems associated to machining of Al and Aluminium Metal Matrix Composites are presented in this section.

Machining of Aluminium

Aluminium (Al) and Al alloys are very found machineable of all the basic materials. The low melting temperature of the material and the higher thermal coefficients of expansion along with relative softness and elasticity make it necessary to disseminate the generated heat. Else, it is difficult to keep up tolerances of the workpiece. Al alloys normally have significant measures of Si, causing them to be adhesive, leading to quick heat formation resulting in chip welding and built up edge.18 At the point when contrasted with alternate materials, the machining of Al combinations is much easier as it is a comparatively soft material, thus resulting in a longer tool life and much reduced cutting forces. Be that as it may, notwithstanding these properties, for an agreeable result, alternate components that additionally must be fulfilled are the issues of material adhesion and also the development of BUE that reduces the tool life and causes other machining issues.Subsequently, optimized tool geometry as well as the machining parameters is highly recommended for the machining of Al and its Al alloys in order to accomplish proper results.19

Machining of Amcs

Aluminium Matrix Composites (AMCs) are extremely difficult to machine due to their abrasive properties and the wear rate of the tools is also high, so that machining is extremely expensive.20 The evaluation of machining of SiC reinforced aluminium matrix composite showed that initial flank wear on brazed polycrystalline diamond and chemical vapour deposition diamond coated tools were generated by abrasion due to the presence of very hard SiC particles.21 For proper machining of Al/SiCMMC at high speed and low depth of cut, without BUC or flank BUC, the rhombic and fixed circular toolings are most effective tooling systems [22].During machining of Al (Situ Al4C3) metal matrix composite, elemental and arc chips formation were observed and hardness increased due to high volume fraction of situ Al4C3in the MMC. It resulted in a decrease in the formation of BUE but increased the surface quality at high cutting speeds.23 Diamond tools are reasonably suitable for MMC machining. Furthermore, diamond coatings appeared to be more economically viable than PCD for MMC machining.24 The machining of MMCs has been difficult due to the extremely abrasive nature of the reinforcements and presents a significant challenge to the industry.25 During machining of Al-Al2O3MMC it was found that at lowercutting speeds and due tolack of formation of a lubricating layer, the friction between the abrasive particle and the cutting tool can be reduced. The tool life was increased, under wet conditions, whenturning at higher speeds. However, the surface quality was disintegrated, due to the flushing away of the partially debonded particulates from the machined surface. In this manner, higher rate of pit gaps and voids were formed.26 The cutting force during machining of AMC is based on particle fracture, ploughing and chip generation. Thus the resistance offered by SiC particles against fracture, ploughing out and makes it difficult to machine.27 The surface roughness values were predicted experimentally using fuzzy logic modelling technique in drilling of Al-SiC composite. The feed is the primary parameter which affects the surface roughness of Al-SiC composite, followed by point angle, tool material, speed and cutting environment.28 When machining the (Ti) MMCs, the tool wear at the initial wear system was completely different from the steady wear system. During the initial wear period, the adhesion is the most essential wear mechanism under all exploratory cutting conditions. At the main snapshot of machining, the impact of accelerated cutting force and temperature gradient promptly to high stress and friction between the cutting tool and material surfaces; hence, the tool layer damage.29 During machining of Hybrid Metal Matrix Composite, the surface roughness mainly depends on the feed rate followed by the cutting speed. Influence of the approach angle is less on the surface roughness of the metal matrix composite.Optimization of machining parameters, nose radius and operation conditions were very important for minimizing the tool wears; maximizing the metal removal rate and better machinability.30 Machining can be improved by the application of MQL

From the machining study, it is revealed that machining of prepared composite is tough because of the abrasive nature of the hard particles. It also found from the review of the literature that the use of coolant during turning of composites increases wear of the tool and surface roughness. The flank wear rate is higher at lessen cutting speed due to the producing of high cutting forces and formation of BUE during traditional machining of prepared composites. The hard reinforced particles in the composites do not part off during machining at low cutting speed by the action of the cutting tool edge. Its rolls over the cutting tool edge and plough over the machined surface, which may cause of creation of high cutting force and formation of poor surface finish. Low feed and low cutting speed gives lower flank wear and thus better tool life in both coated and uncoated inserts when machining the prepared metal matrix composites. Flank wear of coated tool is less when compared with the uncoated insert.

Wear Behaviour of Aluminium Matrix Composites

Wear stands out amongst the most important mechanical issue where the material is influenced principally by speed, naturalconditions, and working load.31 Wear is a moderate and dynamic loss of material which is subjected to rehashed rubbing activity. Wear causes a tremendous measure of use by repairing or supplanting the well used out parts or hardware.32 Aluminium matrix composites reinforced with in situ AlB2 particles were successfully fabricated by powder metallurgy. The wear resistance of the pure aluminium is improved significantly due to the formation of in situ AlB2 particles. The friction coefficient and wear area of the samples also increase almost linearly with the increase in the loadapplied.33 The wear resistance of metal matrix composite depends chiefly on different microstructural qualities like molecule size, volume part, dispersion of reinforced material, and shape.34–38 Among the different types of reinforcements, particulate type of ceramics reinforced with AMCs have alluring and appealing properties like ease of fabrication, higher working temperature and oxidation resistance contrasted with different geometries of reinforcement, for example, fibres and particulates.35 The application of AMCs is restricted due to poor wear resistance under dry lubrication conditions.36–37 The increase in wear rate was reported due to increase in the metallic intimacy with increased load and the coefficient of friction of composite is lower as compared to the Al alloy at low values of the load. 39-40 The load, slidingspeed and weight %age of reinforcement affected the coefficient of friction, where the sliding distance had no effect on it during dry sliding wear tests on Al–SiC–Gr hybrid MMC.41 Wear behaviour can be improved by the application of MQL because of reducing the cutting zone temperature.

Machining of Materials By Mql

Points of interest of MQL helped machining are: Lubricant as a fluid supplied to the workpiece/tool interference is less so there is no need of fluid preservation and disposal42; lessening60% of solid waste, water use by 90%, and aquatic toxicity by 80% due to delivery of lubricants in air instead of water43; diminished coolant costs due to low utilizationof cutting fluid, nontoxic and hazardous effects as mostly vegetable oils are used44; lessened cleaning expense and timedue to low residue of lubricant on chip, tool and work-piece45; better visibility of cutting processing.46 With increasing cutting speed, the average chip thickness decreased regardless of the feed during turning with WC cutting tool. Surface roughness is assumed to be better because of low chip thickness observed due to reduced vibration and lessen power consumption, [45].The cutting performance of MQL machining is superior to that of dry machining in light of the fact that MQL gives the advantagesmainly by reducing the cutting temperature,reduced tool wear, improved tool life and better surface finish as compared to dry machining.Surface finish and dimensional accuracy enhanced mostly because of decrease of wear and harm at the tool tip by the use of MQL 47. Whenthe cooled air MQL technique in finish turning of Inconel 718 is applied, it results in drastic reduction of tool wear and surface roughness and significant improvement in chip shape.40 The MQL technique used for machining of Inconel 718 with three different types of carbide tools depicted that the application of MQL enhances the tool life to a considerable level in comparison with the dry condition. It was also found that the argon gas as a carrier gas of oil mist instead of air provides better cooling to the cutting point.48 It is therefore resumed that, the MQL condition will be a very good alternative to flooded coolant/lubricant conditions if MQL is employed properly.Not only the machining will be environmental friendly but also it will improve the machinability characteristics.49 The different cooling strategies investigated on titanium Ti-6AL-4V bring out that although shorter chips are produced with cooling air condition but chip curl cannot be promoted.49 The application of MQL on the turning of AISI 13 concluded that adopting MQL technique is better option than dry and wet machining;200 ml/h came out to be optimal value of the lubrication.50 The performance of MQL using CBN tool during hard turning of AISI 4340 was studied, the result indicated that application of MQL techniques leads to 40% decrease in cutting forces, 36% decrease in cutting temperature and there is 30% improvement in surface finish.51 The minimum cutting fluid applications enhance the cutting performance and also improve the surface finishduring turning of OHNS steel.57 MQL provides these benefits mainly by reducing the cutting temperature, which improves cooling effect and results in better surface finish.52 MQL is a better option than Wet machining if the machining is to be conducted at higher speed and feed rates. MQL reduced the friction at the tool-work piece interference.53 The flow Penetration into the cutting zone was dependant on the flow velocity and number of nozzles and the most effective MQL performance is with the three nozzle arrangement having aconstant rate of mass flow.54

It is evident from above literature that minimizing the uses of harmful cutting fluids is of dire necessity which has led innumerable researcher towards investigating the MQL during machining of materials irrespective of the machining process.54 The continuous MQL supply showed better results in terms of tool life rather than an intermittent MQL supply.53 Application of MQL system reduced the cutting zone temperature leading to reduced wear. The use of MQL system using vegetable fluids in the lubrication of A306 cast Aluminium alloy resulted in reduced cost of recycling, storage and waste disposal. Also decreased the temperature during the process and increased the life cycle of the tools.55 Vegetable oil performed better lubrication performance as compared with liquid paraffin MQL because vegetable oil MQL has a low friction coefficient with high viscosity and surface tension achieved low thermal flux.56 Under unlubricated condition, due to lower the friction coefficient of TiAl-TiB2 materials is significantly decreases the wear rate in sea water.The friction coefficient of TiAl-TiB2 materials in sea water is insignificantly related with the amount of TiB2, but their wear resistance increases with the increase of TiB2 content and is superior to the TiAl alloy. The enhanced wear resistance for the composites is inferable from the high hardness and moderately poor corrosion resistance, which is helpful to the formation of the defensive oxidation-corrosion film.57

The literature reveals that applications of MQL has resulted in better tool life, enhanced surface finish, lessening in cutting temperature, reduced cutting forcesandbetter chip forms. As number of factors are included in MQL helped machining, a watchful choice of parameters is required to make the procedure viable and productive. Appropriate combination of cutting parameters is must to guarantee proper chip removal and departure for effective functioning of MQL.

Conclusions

It is evident from the literature that for machining of hard material under MQL condition makes use of four kinds of tools coated tungsten carbide (WC), cermet, Polycrystalline diamond (PCD) and cubic boron nitrite (CBN). However these combinations of MQL and above mentioned tools are largely devoted to low speed machining. Although some scattered works are seen in area of machining of composites under MQL conditions but no significant research is seen. An investigation of the tool wear and expected tool life with higher cutting speed and feed rate but minimal depth of cut is still to be compressively evaluated. When it comes to metallic composites, the hard natures of the reinforcements make it even difficult to machine under dry conditions and it adversely affects the tool as well as the machined surface.

The composition of reinforcement material in MMCs is particularly less than 40%. The most commonly used MMC material is the reinforcement of SiC particles in an aluminium matrix. Further combinations include titanium and magnesium alloys with Silicon Carbide (SiC), boron carbide (B4C) or alumina (Al2O3). The machining of these materials becomes a laborious task due to the highly abrasive nature of reinforcements used in them. The presence of hard abrasive reinforcement particles during machining operations results in working tool to wear quickly. It thus becomes necessary to characterize the machining in perspective of required tool material selection, machining conditions, machinability and their impacts on tool life by the use of MQL on MMC.

References

- Hashim J., Looney L., Hashmi M. S. J. The wettability of SiC particles by molten aluminum alloy. Journal of Materials Processing Technology. 2000;119(1-3):324-328.

CrossRef

- Hashim J., Looney L., Hashmi M. S. J. Particle distribution in cast metal matrix composites—Part I [J]. Journal of Materials Processing Technology. 2002;123:251−257.

CrossRef

- Ezugwu E., Bonney J.,Yamane Y. An overview of the machinability of aeroengine alloys. Journal of Materials Processing Technology. 2003;134:233–253.

CrossRef

- Jaffery S. I., Mativenga P. T. Assessment of the machinability of Ti–6Al–4V alloy using the wear map approach. The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology. 2008;40:687–696.

CrossRef

- Yuan S. M., Yan L. T., W. Liu D and Liu Q. Effects of cooling air temperature on cryogenic machining of Ti-6Al-4V alloy. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2011;211(3):356–362.

CrossRef

- Hong S. Y., Ding Y. Micro-temperature manipulation in cryogenic machining of low carbon steel. Journal of Materials Processing Technology. 2001;116:22–30.

CrossRef

- Hong S. Y., Ding Y., Ekkens R. G. Improving low carbon steel chip breakability by cryogenic chip cooling. International Journal of Machine Tools and Manufacture. 1999;39:1065–1085.

CrossRef

- Kakinuma Y., Yasuda N., T. Aoyama, “Micromachining of soft polymer material applying cryogenic cooling,” Journal of Advanced Mechanical Design, Systems, and Manufacturing. 2008;2:560–569.

CrossRef

- C. Lin, Y. Hung, W.C. Liu, S.W. Kang, “Machining and fluidity of 356Al/SiC (p) composites,” Journal of Materials Processing Technology. 2001;110:152–159.

CrossRef

- M. El-Gallab, M. Sklad, “Machining of Al/SiC particulate metal–matrix composites: Part I: Tool performance,” Journal of Materials Processing Technology. 1998;83:151–158.

CrossRef

- L. Yuan, J. Han, J. Liu, and Z. Jiang, “Mechanical properties and tribologicalbehavior of aluminum matrix composites reinforced with in-situ AlB2 particles,” Tribol. Int. 2016;98:41–47.

CrossRef

- Chalmers, R.E, “Global Flavor Highlights NAMRC XXVII”, Manufacturing Engineering. 1999;123(1)80-88.

- D. Priyadarshi and R. K. Sharma, “Effect of type and percentage of reinforcement for optimization of the cutting force in turning of Aluminium matrix nanocomposites using response surface methodologies,” J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 2016;30(3):1095–1101.

CrossRef

- F. Klocke, G. Eisenblatter: Dry Cutting, Annals of the CIRP. 1997;46(2)519.

CrossRef

- MaClure, T.F., Adams, R., and Gugger, M.D, “Comparison of Flood vs. Micro- Lubrication on Machining Performance”, Website: http://www. Unist.com/techsolve.html. 2001.

- AmanAgarwal, Hari Singh, Pradeep Kumar, Manmohan Singh, “Optimisation of power consumption for CNC turned parts using response surface methodology and Taguchi’s technique – a comparative study,” J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2008;200:373–384.

CrossRef

- Astakhov, V.P,“Ecological machining: near-dry machining,” J.P. Davim (Editor): Machining Fundamentals and Recent Advances, Springer: London. 2008.

CrossRef

- Ozben T, Kilickap E, ÇakIr O, Investigation of mechanical and machinability properties of SiC particle reinforced Al-MMC, J Mater Process Tech. 2008;198(1–3):220–225.

CrossRef

- Wang J, Huang CZ, Song WG, The effect of tool flank wear on the orthogonal cutting process and its practical implications. J Mater Process Tech. 2003;142(2):338–346.

CrossRef

- S. Durante, G. Rutelli, and F. Rabezzana, “Aluminum-based MMC machining with diamond-coated cutting tools,” Surf. Coatings Technol. 1997;94–95:632–640.

CrossRef

- C. J. E. Andrewes, H. Feng, and W. M. Lau, “Machining of an aluminum / SiC composite using diamond inserts,” J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2000;102:25–29.

CrossRef

- A. Manna and B. Bhattacharayya, “A study on machinability of Al/SiC-MMC,” J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2003;140(1–3)SPEC:711–716.

- Y. Ozcatalbas, “Chip and built-up edge formation in the machining of in situ Al4C3-Al composite,” Mater. Des. 2003;24(3):215–221.

CrossRef

- Y. K. Chou and J. Liu, “CVD diamond tool performance in metal matrix composite machining,” Surf. Coatings Technol. 2005200(5–6)1872–1878.

- S. Kannan and H. A. Kishawy, “Surface characteristics of machined aluminium metal matrix composites,” Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 2006;46(15):2017–2025.

CrossRef

- S. Kannan and H. A. Kishawy, “Tribological aspects of machining aluminium metal matrix composites,” J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2008;198(1–3):399–406.

CrossRef

- D. Priyadarshi and R. K. Sharma, “Effect of type and percentage of reinforcement for optimization of the cutting force in turning of Aluminium matrix nanocomposites using response surface methodologies,” J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 2016;30(3)1095–1101.

CrossRef

- AnandBabu, G. Vijaya Kumar, and P. Venkataramaiah, “Prediction of Surface Roughness in Drilling of Al 7075/10% – SiCp Composite under MQL Condition using Fuzzy Logic,” Indian J. Sci. Technol., vol. 8, no. 12, 2015.

- X. Duong, J. R. R. Mayer, and M. Balazinski, “Initial tool wear behavior during machining of titanium metal matrix composite (TiMMCs),” Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2016;60:169–176.

CrossRef

- M. A. Xavior and J. P. A. Kumar, “Machinability of Hybrid Metal Matrix Composite – A Review,” Procedia Eng. 2017;174:1110–1118.

CrossRef

- F. Ficici, S. Koksal, R. Kayikic, and O. Savas, “Investigation of lubricated sliding wear behaviors of in-situ ALB2/AL Metal Matrix composite,” Advanced Composite Letters. 2011;20(4):109–116.

- M. P. Kumar, K. Sadashivappa, G. P. Prabhukumar, and S. Basavarajappa, “Dry sliding wear behavior of garnet particles reinforced zinc-aluminium alloy metal matrix composites,” Materials Science. 2006;12:209–213.

- L. Yuan, J. Han, J. Liu, and Z. Jiang, “Mechanical properties and tribologicalbehavior of aluminum matrix composites reinforced with in-situ AlB2 particles,” Tribol. Int. 2016;98:41–47.

CrossRef

- Y. Kamata and T. Obikawa, “High speed MQL finish-turning of Inconel 718 with different coated tools,” J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2007;192–193:281–286.

CrossRef

- D. V Lohar and C. R. Nanavaty, “Performance Evaluation of Minimum Quantity Lubrication ( MQL ) using CBN Tool during Hard Turning of AISI 4340 and its Comparison with Dry and Wet Turning,” 2013;3(3):102–106.

- N. Banerjee and A. Sharma, “Identification of a friction model for minimum quantity lubrication machining,” J. Clean. Prod. 201483:437–443.

CrossRef

- V. S. Sharma, G. Singh, and K. Sørby, “A Review on Minimum Quantity Lubrication for Machining Processes,” Mater. Manuf. Process. 30(8):935–953.

CrossRef

- S. Zhang, J.F. Li, J. Sun, F. Jiang, “Tool wear and cutting forces variation in high-speed end-milling Ti–6Al–4V alloy,” The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology. 2009;46:69–78.

CrossRef

- S. R. Filho, “Comparison among different vegetable fluids used in minimum quantity lubrication systems in the tapping process of cast aluminium alloy,” J. Clean. Prod. 2017;140:1255–1262.

CrossRef

- B. Bhushan, Modern Tribolgy Handbook, CRC Press, Boca Raton, Fla, USA. 2001.

- V. N. Gaitonde, S. R. Karnik, and M. S. Jayaprakash, “Some studies on wear and corrosion properties of AL5083/Al2O3/graphite hybrid composites,” Journal of Minerals and Materials Characterization and Engineering. 2012;11(7):695–703.

CrossRef

- M. Kozma, “Friction and wear of aluminum matrix composites,” in Proceedings of the National Tribology Conference, The Annals of the University “Dunarea de Jos” of Galati, fascicle. 2003;99–106

- K. Ravi Kumar, K. M. Mohanasundaram, G. Arumaikkannu, and R. Subramanian, “Analysis of parameters influencing wear and frictional behavior of aluminum-fly ash composites,” Tribology Transactions. 2012;55(6):723–729.

CrossRef

- L. Zhang, X. B. He, X. H. Qu, B. H. Duan, X. Lu, and M. L. Qin, “Dry sliding wear properties of high volume fraction SiCp/Cu composites produced by pressureless infiltration,” Wear. 2008;265:(11-12):1848–1856.

CrossRef

- C. A. Brown and M. K. Surappa, The machinability of a cast Aluminium alloy-graphite particle composite, Mater. Sci. Eng. A. 1988;102:31-37.

CrossRef

- S. Zhiqiang, Z. Di, L. Guobin, Evaluation of dry sliding wear behavior of silicon particles reinforced aluminum matrix composites, Materials and Design. 2005;26:454-458.

CrossRef

- S. Suresha, B.K. Sridhara,Materials and Design34. 2012;576-583.

CrossRef

- Dasch, J. M. &Kurgin, S. K, “A characterization of mist generated from minimum quantity lubrication (MQL) compared to wet machining,” International Journal of Machining and Machinability of Materials, 7(1/2), 8295, 2010.

CrossRef

- Clarens, A.F.; Zimmerman, J. B.; Keoleian, G. A.; Hayes, K. F. &Skerlos, S. J. “Comparison of life cycle emissions and energy consumption for environmentally adapted metalworking fluid system,” Environmental Science and Technology, 2008;42(22):8534-8540.

CrossRef

- M. M. A. Khan, M. A. H. Mithu, and N. R. Dhar, “Journal of Materials Processing Technology Effects of minimum quantity lubrication on turning AISI 9310 alloy steel using vegetable oil-based cutting fluid,” 2009;209:5573–5583.

- Attanasio, A.; Gelfi, M.; Giardini C. &Remino C. “Minimal quantity lubrication in turning: Effect on tool wear,” Wear. 2006;260:333-338.

CrossRef

- Z. Tekiner and S. Yeşilyurt, “Investigation of the cutting parameters depending on process sound during turning of AISI 304 austenitic stainless steel,” Mater. Des. 004;25(6):507–513.

- Khan M.M.A., Dhar N.R., “Performance evaluation of minimum quantity lubrication by vegetable oil in terms of cutting force, cutting zone temperature, tool wear, job dimension and surface finish in turning AISI-1060 steel,” Journal of Zhejiang University science. 2006, aissn 1009-3095,1862-1775.

- Sreejith PS, Ngoi BKA. “Dry machining: machining of the future. Journal of Material Processing Technology. 2000;101:287-91.

CrossRef

- S. M. Hafis, M. J. M. Ridzuan, A. R. Mohamed, R. N. Farahana, and S. Syahrullail, “Minimum Quantity Lubrication in Cold Work Drawing Process: Effects on Forming Load and Surface Roughness,” Procedia Eng. 2013;68:639–646.

CrossRef

- S. B. Kedare, D. R. Borse, and P. T. Shahane, “Effect of Minimum Quantity Lubrication ( MQL ) on Surface Roughness of Mild Steel of 15HRC on Universal Milling Machine,” Procedia Mater. Sci. 2014;6:150–153.

CrossRef

- L. Wang, J. Cheng, Z. Qiao, J. Yang, and W. Liu, “Tribological behaviors of in situ TiB2insitu ceramic reinforced TiAl-based composites under sea water environment,” Ceram. Int. 2016;0–1.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

, H. S. Bains2, Sumit Jain3 and D. Priyadarshi1

, H. S. Bains2, Sumit Jain3 and D. Priyadarshi1 Material Science Research India An International Peer Reviewed Research Journal

Material Science Research India An International Peer Reviewed Research Journal